Disconnected from interest rates

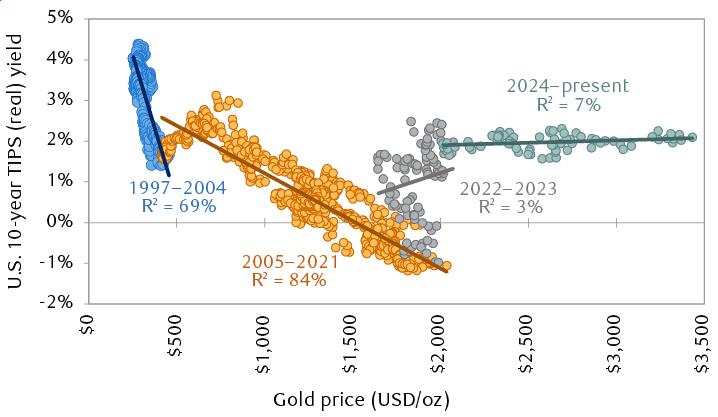

Identifying what exactly drives the price of gold has always been a challenge. Yet one relationship that has held up reasonably well over the past 25 years is gold’s inverse correlation with real interest rates.

Gold generates no cash flow. Given that holding gold involves costs—storage and insurance—gold’s “income yield” is arguably negative. This makes gold sensitive to changes in real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. When real rates rise, the opportunity cost of holding gold increases, reducing its appeal relative to income-generating assets. When real rates fall, the reverse is true.

From the late 1990s until 2021, this dynamic underpinned a relatively stable relationship. Periods of low or falling real interest rates—proxied by the yield on U.S. 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS)—have typically been conducive to a favourable environment for gold.

Since 2022, however, the pattern has weakened substantially. Despite a sharp rise in real interest rates during 2022 and 2023—as central banks hiked rates rapidly to rein in post-pandemic inflation—gold prices remained resilient. More recently, gold has rallied further, even as real yields have remained flat.

The relationship between gold and real interest rates

The chart shows the statistical coefficient of correlation (R-squared) between the price of gold and the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) since 1997. From 1997 through 2004, TIPS yields ranged from roughly 1% to 4.5%, and the coefficient of correlation was 69%. From 2005 to 2021, yields ranged from roughly -1% to 3%, and the correlation was 84%. In 2022 and 2023, yields ranged from roughly -1% to 2.8%, with a correlation of just 3%. Since 2024, yields have stayed around 2% and the correlation is 7%.

Note: R2 denotes the coefficient of determination, a statistical measure of the extent to which changes in gold prices can be accounted for by changes in real interest rates in this analysis.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; weekly data through 6/20/25

New drivers for a new regime?

Gold, like any asset, is influenced by supply and demand. However, the relatively inelastic nature of gold supply—global mine production has grown at just two percent annually since 2010—tends to put the focus squarely on demand-related variables.

Gold’s appeal spans several functions. It is viewed variously as a store of value, a central bank reserve asset, and a portfolio diversifier. This wide range of roles has long set gold apart, requiring a different analytical framework. The forces driving demand often vary depending on the broader macro backdrop.

With the inverse correlation between gold and real rates, which has held for much of the past two decades, no longer intact, a shift in the underlying factors shaping gold’s trajectory may be underway. Understanding who the marginal buyer is—and why they are buying—has become increasingly important.

In recent years, central banks have emerged as a sizeable, and relatively price-insensitive, source of demand. Their renewed interest stems in part from geopolitical considerations, notably the freezing of Russia’s foreign-currency assets in 2022, which underscored the vulnerability of holding U.S. dollar-based assets as central bank reserves. Since then, central banks—especially in emerging markets—have sought to gradually diversify their reserve assets by building their allocations to gold.

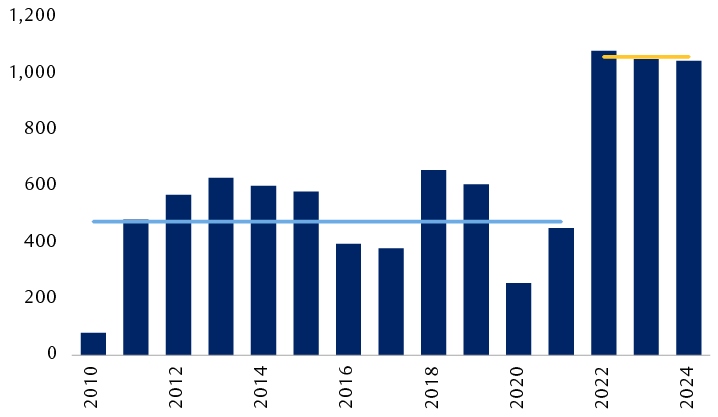

Central bank net purchases of gold have exceeded 1,000 tons for three consecutive years, double the average between 2010 and 2021, and have helped offset relatively softer investment demand. This trend seems likely to persist: a recent survey of 72 monetary authorities conducted by the World Gold Council found that virtually all (95 percent) of the respondents expect “official sector” gold holdings to increase over the next year, suggesting central banks will continue to accumulate bullion in the years ahead.

Central banks have increased their gold allocations

Tons of gold purchased annually by central banks

The chart shows the amount of gold purchased by global central banks annually since 2010. From 2010 through 2021, central banks purchased an average of 473 tons of gold annually. In 2022, 2023, and 2024, total purchases increased to over 1,000 tons per year.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, World Gold Council

Two other structural factors could further support demand: portfolio diversification and a store-of-value alternative. The retreat of U.S. global leadership—evident in the Trump administration’s desire to prioritize domestic issues—has coincided with a more fragmented geopolitical landscape. A more splintered world marked by more frequent conflict, combined with growing concerns over elevated government debt levels and questions about the long-term role of the U.S. dollar in the international system, could strengthen the case for gold as a diversifier against persistently elevated levels of uncertainty.

The fading explanatory power of real interest rates suggests to us that these alternative drivers are now playing a larger role in shaping the gold market.

Investment takeaways

Few financial assets divide opinions as sharply as gold. The absence of cash flows makes it difficult to value using conventional methods, leaving the precious metal without a fundamental valuation anchor. Even so, gold has long drawn support from its role as a hedge against crisis risk and as an alternative to other currencies.

Gold’s appeal also stems from its diversification benefits. It tends to have low correlation with equities, and this characteristic becomes particularly valuable in two scenarios: first, during periods of acute economic or financial market stress; and second, when stocks and bonds move in tandem. The latter condition—rare over the past two decades—has become more common in the current environment of more volatile inflation.

In our view, gold is better suited as a strategic allocation than a tactical one. Attempting to time price rallies—or anticipate which global events might trigger them—is inherently difficult. A long-term, strategic approach is more likely to capture gold’s full potential benefits. That means accepting periods of underperformance in exchange for the potential protection and diversification that gold may offer when they are needed most.