Following is an executive summary of the complete “How BRICS sees the world” report, which is part of RBC’s ongoing “Worlds apart” series exploring trade fragmentation and deglobalization risks, along with their ramifications for economies and investors.

A world in transition

There are signs the world is transitioning from a U.S. led Western unipolar order which had characterized much of the post-Cold War period, to a new multipolar framework where not only the U.S. and its Western allies shape global affairs, but other countries outside the West also have significant influence.

The intensifying strategic partnerships among BRICS countries are natural, predictable outgrowths of the ongoing shifts in the geopolitical and geo-economic orders.

Whether the post-Cold War “rules-based” international order can be extended amid these changes is up for debate and is a controversial topic in Washington, understandably. Analysts at the West’s leading interventionist-oriented foreign policy think tanks push back against the multipolar narrative and assert that the U.S. maintains its dominant role and primacy (aka hegemony).

Nevertheless, some prominent Americans, including retired General and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley, have acknowledged at least since 2023 that the multipolar world is already here.

The BRICS association, along with its cousin Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) entity—both of which include the large Eurasian troika of China, Russia, and India—are attempting to chart a new multipolar course.

A bigger BRICS

BRICS has been expanding amid the geopolitical changes. It has grown from five members in 2023 to 10 members and 10 partners in 2025.

Members are Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

BRICS is not designed to be a formal economic and political bloc like the EU. Its members flatly reject the term “bloc.”

Nor is it designed to be a formal military security alliance like NATO or what is emerging in the EU. There is no military component whatsoever.

Public statements have made it clear that BRICS countries desire deeper trade, financial, strategic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with each other, and want to leverage the economic achievements that are already under their belts and may be ahead.

We assess that the association is only getting started and has the potential to integrate and expand further.

Economic heft = Geopolitical clout

When measured in U.S. dollars, BRICS members represent five of the 20 largest economies in the world.

But when GDP is calculated by purchasing power parity (PPP), which attempts to adjust for the cost of living, BRICS member countries move higher in the ranks, representing five of the top eight economies.

In 2025, the 10 BRICS members are expected to make up almost 40 percent of global GDP compared to 28 percent for G7 nations, based on PPP calculations by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This gap is forecast to widen through 2030.

We think BRICS is too big to ignore.

BRICS economic clout to increase further

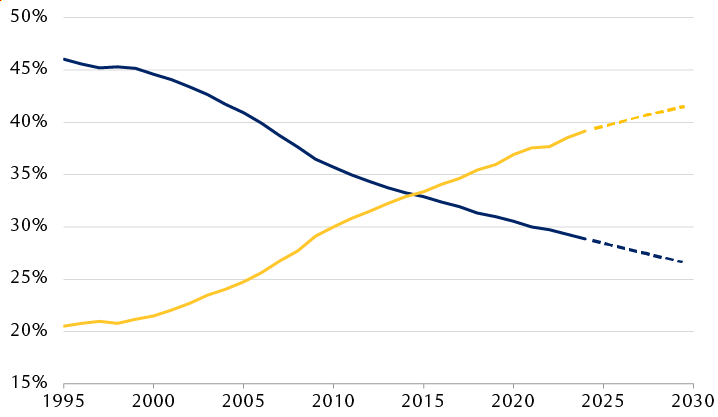

Share of global GDP based on purchasing power parity in international dollars

GDP of the 10 BRICS members surpassed G7 GDP in 2015, and the IMF expects the gap to widen further. Even before BRICS membership expansion in 2024 and 2025, the previous five BRICS members had surpassed the G7 in 2019.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, International Monetary Fund; data as of 9/11/25; 2025–2030 are IMF projections

The line chart shows the proportion of global GDP contributed by the G7 group of nations and by 10 BRICS member countries annually from 1995 through 2030 based on purchasing power parity; data from 2025 through 2030 are based on International Monetary Fund (IMF) projections. In 1995, there was a very wide gap between the two groups with the G7 at 46% and BRICS at 20.5%. The G7's GDP as a proportion of global GDP has declined meaningfully since then, while the BRICS countries' proportion of global GDP has steadily climbed. The IMF projects this trend will continue through its forecast period of 2030. The 10 BRICS countries' share of global GDP surpassed the G7 in 2015 when BRICS reached 33.4%. By 2024, the G7 share had declined to 28.9% and BRICS had increased to 39.2%. By 2030, the IMF projects the G7 share will decline to 26.3% and BRICS will rise to 41.8%.

A BRICS currency is a red herring for now, but other currency initiatives are not

Despite significant press and blog attention over the years about the potential creation of a single BRICS currency, this is still not formally being considered.

However, three BRICS currency-related initiatives could further reduce the proportion of global trade in U.S. dollars and within the Western-backed SWIFT payments network.

- Trading in national currencies: Members want to expand bilateral trade in their own currencies (aka “local currencies”) and improve financial and banking system plumbing to make this easier and more efficient. This trend picked up pace among BRICS countries and others following economic sanctions on Russia related to the Ukraine crisis.

- BRICS Cross-border Payments Initiative: Members seek to fortify and enhance their own interbank communications systems and provide an additional alternative to SWIFT that cannot be disrupted by Western governments’ sanctions.

- BRICS Grain Exchange: Members are creating a new commodity exchange to trade grain and seek to subsequently expand into other agriculture products and commodities. Agriculture commodity trading has been dominated by the U.S. and other Western exchanges for decades, which effectively set prices globally, and where much of the goods are traded in U.S. dollars. The BRICS Grain Exchange would be an alternative, with the ability to trade in local currencies.

BRICS countries repeatedly emphasize they are firmly against using currencies—the U.S. dollar in particular—as a foreign policy weapon, and this shapes their currency-related initiatives.

The heartbeat of BRICS: Bilateral trade, investment, and cooperation

BRICS is not a panacea for any of the countries involved.

However, by participating in the association, countries have many more opportunities to engage in bilateral investment, trade, and diplomatic discussions, and people-to-people exchanges, than they otherwise would if the association didn’t exist.

For example, the recent progress between China and India to resolve their longstanding border dispute and improve relations has been facilitated by BRICS and SCO participation.

The entrance of Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian countries into the broader BRICS association in 2024 and 2025—particularly the UAE, Indonesia, and Malaysia—has enhanced the group notably and opened many more economic opportunities, in our assessment.

The involvement of these regions, along with those in Africa and Latin/South America, integrates BRICS more deeply into the so-called “global majority.”

BRICS and the SCO are becoming leading platforms for “Global South” countries to have a bigger voice in world affairs. This will likely be BRICS’ focus in 2026 when India assumes the rotating presidency.

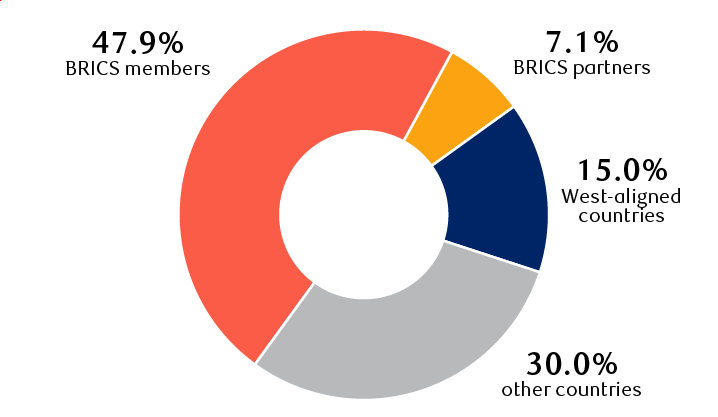

BRICS groups represent more than half of the world’s population

Percentage of world population based on United Nations 2025 estimates

West-aligned countries are the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, the European Union (27 countries), Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand. BRICS groups based on 10 member and 10 partner countries.

Source - RBC Wealth Management; data as of 7/2/25 based on United Nations Population Division estimates for all countries, except EU countries based on Trading Economics’ projections

The area chart shows the following population groups as a percentage of global population: BRICS members, 47.9%; BRICS partners, 7.1%; West-aligned countries, 15.0%; other countries, 30.0%.

The soul of BRICS: Sovereignty

BRICS members and partners have specific domestic development programs in multiple directions to shore up their own sovereignty and national security, some backed by big fiscal spending. These include technological, energy, agriculture, health, metals/minerals, and financial security initiatives. Ironically, America under Trump 2.0 is also attempting to shore up its own sovereignty in many of the same areas.

BRICS’ priority on sovereignty was recently demonstrated by the most active and intense level of coordination between and among members that we have seen in the association’s history.

This occurred after the Trump administration threatened and then imposed extra tariffs on Brazil due to disagreements about the country’s domestic political and judicial affairs, and on India for geopolitical reasons due to its relations with Russia and purchases of Russian crude oil during the Ukraine crisis.

India and Brazil strongly pushed back against these tariffs, citing violations of their sovereignty. China also stated multiple times that it would not succumb to pressure regarding its trade relations with Russia or any other country.

These events and other tariff threats on the association as a whole caused quite a stir within and among BRICS countries because they are viewed as de facto economic sanctions.

We think any use of “tariffs as sanctions”—whether by the U.S., European countries, or other Western nations—could continue to backfire.

The fallout from these disputes and high tariff rates in general are hastening integration within BRICS and the SCO, and we think these issues will ultimately incentivize more countries to push harder to achieve a multipolar global order sooner rather than later.

Investing in the shift toward a multipolar world

BRICS’ ongoing integration and development, combined with increasing U.S. trade protectionism since 2018, reinforces our belief that a potential shift to a multipolar, more fragmented world order argues for a new way of thinking.

Investment portfolio allocations should be viewed through a different lens. Sub-asset class allocations within equities and fixed income should no longer be assessed through the lens of cooperative globalization that occurred in previous decades, as we don’t think that era is coming back anytime soon.

This translates into three practical implementations in investment portfolios:

- We believe this new era begs for more active asset management of country, industry, and company investment exposures.

- We recommend investors diversify geographically. For investors in North America, we suggest maintaining less of a “home bias” or “regional bias” allocation in equity and fixed income portfolios than in years past and would consider increasing allocations to international stocks and bonds. We believe all investors should take a close look at allocations to Asia and emerging markets to determine if they are sized appropriately, up to at least the long-term recommended strategic allocation level.

- On the stock side of portfolios, regardless of region, we still suggest including exposure to equity industries geared toward sovereign development.

For in-depth information, including a list of industries that could benefit, please review the full report: How BRICS sees the world.