- The growth and inflationary impact of tariffs can follow an “up-and-then-down” sequence.

- As higher prices eat into purchasing power and dampen demand, growth momentum tends to subside and the overall effect on economic activity is negative.

- There is a risk that tariffs could be longer-lasting if they are viewed as a key source of revenue.

Economic resilience fades

Taxes on imports (aka tariffs) can generate revenue, shield domestic industries, or gain leverage in trade negotiations. While the immediate economic effects can be stimulative, the longer-term consequences can prove less benign.

Shorter term, tariffs can boost economic activity as firms and consumers front-load purchases in anticipation of higher costs. However, this flurry often gives way to an “air pocket,” as demand is merely pulled forward while higher prices and retaliatory measures dampen export prospects. Business investment, particularly in manufacturing, often falters as uncertainty mounts.

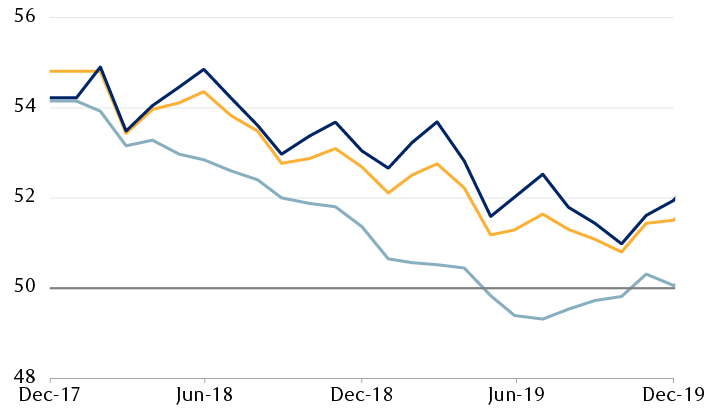

In the earlier mentioned U.S.-China trade war, the global manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) slid into contraction, and business capital spending slowed markedly. Though the services sector weathered the disruption better, the combined drag from weaker consumption and investment trends eventually took a toll on the global economy.

Trade rifts stifled economic momentum

The line chart shows the movements of the JPMorgan Global Composite Purchasing Managers’ Index, the JPMorgan Global Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index, and the JPMorgan Global Services Purchasing Managers’ Index from January 31, 2018 to December 31, 2019. All three indexes trended generally downward over the period shown. The Composite Purchasing Managers’ Index went from approximately 55 to 52; the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index went from approximately 54 to 50; and the Services Purchasing Managers’ Index went from approximately 54 to 52.

Note: A PMI level of 50 separates expansion from contraction.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg

Inflation may follow a similar “rise-and-fall” pattern

The inflationary impact of tariffs can also follow an “up-and-then-down” sequence. Initially, tariffs push prices higher as increased import costs filter through to consumer prices. The past three years indicate businesses will likely try to pass these costs to their customers.

Much depends on the scope of the tariffs—broad measures can drive sharper price increases, while narrowly applied tariffs would likely have a more muted impact. Also, a stronger domestic currency for the country imposing tariffs can ease the inflationary burden by reducing import costs.

Although a lengthy cycle of tit-for-tat tariffs would prolong uncertainty and cost pressures, as higher prices eat into purchasing power and dampen demand, inflationary momentum tends to subside.

In the U.S.-China trade war, inflation accelerated early on but receded over time as consumer and business spending weakened under the strain of trade uncertainties. Meanwhile, a nine percent rise in the trade-weighted U.S. dollar alongside a 13 percent decline in the Chinese yuan, helped soften the upward price pressures.

Trump 1.0 trade war’s impact on inflation was short-lived

The line chart shows consumer inflation expressed as monthly year-over-year change in the U.S. Consumer Price Index and the OECD Major 7 Consumer Price Index from January 31, 2018 to December 31, 2019. U.S. inflation was at 2.1% in January 2018, rose to 2.9% in July 2018, fell to 1.5% in February 2019, and trended unevenly upward to 2.3% in December 2019. OECD Major 7 inflation was 1.8% in January 2018, rose to 2.5% in July 2018, fell to 1.3% in January 2019, and then trended unevenly upward to 1.8% in December 2019.

The OECD inflation measure includes the U.S., Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the UK, and Japan.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg

This time is different, maybe

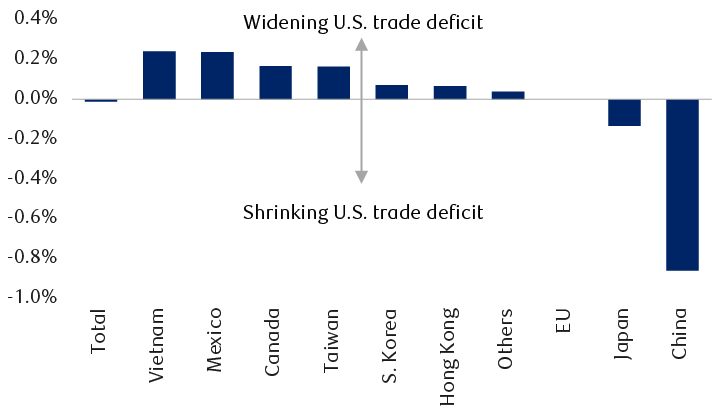

That trade war primarily targeted China, allowing businesses to reroute trade flows and soften the broader economic fallout. Indeed, while tariffs on Chinese imports, which remained in place under the Biden administration, have helped shrink the United States’ goods trade deficit with China, the United States’ overall goods trade deficit is little changed relative to 2016 (as a share of GDP) as importers substituted goods from elsewhere in Southeast Asia and North America.

The U.S.’s shrinking trade deficit with China has been more than offset by wider deficits with other countries

Change in U.S. goods trade deficit (% of GDP, past four quarters vs. 2016)

The bar chart shows the U.S. trade deficit as a percentage of GDP for the past four quarters versus 2016. It shows that the U.S.’s shrinking trade deficit with China has been more than offset by wider deficits with other countries. Total: -0.01%; Vietnam: 0.24%; Mexico: 0.24%; Canada: 0.17%; Taiwan: 0.16%; South Korea: 0.07%; Hong Kong: 0.07%; Others: 0.04%; EU: 0%; Japan: -0.13%; China: -0.86%.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; data through Q3 2024

Donald Trump’s second-term trade policy, however, threatens to put more countries in the tariff crosshairs and make trade diversion more difficult. In 2018, the U.S. average import tariff rose to around three percent from 1.5 percent. If the latest policy proposals are fully enacted, RBC Economics estimates the U.S. average tariff rate could soar into double digits—a level not seen since the 1940s—with economic repercussions dwarfing those of the 2018 trade conflict.

Thus far, it looks like the Trump tariff playbook hasn’t changed much. The administration didn’t impose tariffs on day one, opting instead for a review of foreign trade practices to be delivered April 1. Reciprocal tariffs and plans to re-impose levies on steel and aluminum don’t take effect immediately, leaving room for negotiation with trading partners. Canada, Mexico, and Colombia have been able to defer or avoid tariffs by acceding to U.S. demands. At this point, the administration has only followed through with tariffs on China, at a lower rate than was previously floated.

Duration is key

In addition to the size and scope of tariffs, how long such measures remain in place is key to their economic and inflation impact, in our view. Higher trade barriers might be an enduring feature of the U.S.-China relationship, but tariffs on other trading partners could continue to be more transactional in nature as Trump seeks to leverage the United States’ substantial purchasing power for trade and non-trade objectives.

“Reciprocal tariffs” aim to level the playing field with countries that already impose their own protectionist measures on the United States. If they end up encouraging countries to come to the negotiating table—which is the president’s goal, in our view—the countries could ultimately support global trade by reducing trade barriers. However, dismantling these barriers and opening up domestic industries to greater competition is likely to be a complex process involving many stakeholders and powerful lobbying groups. And whether reciprocal tariffs ultimately reduce the United States’ trade deficit is another matter.

Steel tariffs seek to protect an industry that is seen as vital to economic and national security, but trading partners were able to negotiate exemptions in the past. The U.S. relies heavily on imported aluminum, particularly from Canada, suggesting to us that those tariffs may be a bargaining chip to be used in broader, bilateral negotiations as Trump aims to address any number of trade irritants. Sticking with Canada, long-standing issues such as dairy quotas and softwood lumber, as well as more recent complaints regarding banking access and extraterritorial taxation, could make the country a target for tariffs, but also leave plenty of room for negotiation.

There is a risk that tariffs could be longer-lasting if they are viewed as a key source of revenue, potentially supporting tax cuts in the U.S. or other fiscal objectives, rather than a negotiating tool. For every percentage point increase in the United States’ average tariff rate, annual customs revenue rises by $32 billion, or about 0.1 percent of GDP (the United States’ current budget deficit is around 6.5 percent of GDP). However, that boost might be dampened by import substitution, and offset by lower revenue elsewhere due to a weaker economy. Trump’s unorthodox trade doctrine holds that tariffs are paid for by foreign countries, but the 2018–2019 experience shows that costs tend to fall on U.S. consumers.

Economic starting points

The world economy entered the 2018–2019 U.S.-China trade war on a relatively steadier footing, with real global GDP growth of 3.8 percent year over year in 2017 and consumer inflation for the “Major Seven” developed economies at 1.8 percent. Low inflation and strong growth gave the world economy some leeway to absorb economic shocks. Today, global GDP growth is expected by Bloomberg consensus to slow to three percent this year (from 3.2 percent in 2024), and average consumer inflation for major developed economies is running closer to three percent, above the typical two percent target pursued by major central banks. Unlike in 2018, today’s economy has less room to absorb shocks.

How aggressively the U.S. administration pursues its trade agenda remains uncertain. But we believe tariffs would almost certainly dent demand and weigh on U.S. growth. Selective tariffs—rather than universal ones—still seem like a reasonable base-case scenario to us in light of real-world constraints. Imposing tariffs on politically sensitive energy and food products would run counter to the objective of tackling household affordability challenges. The lack of clarity and predictability means businesses and investors currently face an uncomfortably wide spectrum of potential outcomes.

RBC Global Asset Management cautions that “any estimate unavoidably leaves considerable room for error.” More broadly, however, we think the below estimates corroborate the notion that tariffs are generally “lose-lose” for trading partners and for the countries that implement them. In addition to potential inflationary effects in the short term, tariffs are often met with retaliatory measures.

Economic implications of U.S. tariffs

Estimated maximum cumulative effect on economic output after two years, assuming reciprocal tariffs

| Scenario | Effect on economic output | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Canada | U.S. | Mexico | China | Japan | Eurozone | UK | |

| Original tariff plan: 60% China, 10% rest of world (Likelihood: 10%) | -1.0% | -1.9% | -1.2% | -1.5% | -1.4% | -0.6% | -0.9% | -0.6% |

| North America-focused tariffs: 25% Canada, 25% Mexico, 10% China (Likelihood: 10%) | -0.8% | -4.5% | -1.5% | -4.0% | -0.6% | -0.2% | -0.4% | -0.2% |

| Substantial but temporary tariffs: One of the above scenarios, but tariffs withdrawn after several months (Likelihood: 25%) | -0.3% | -1.0% | -0.4% | -0.9% | -0.3% | -0.1% | -0.2% | -0.1% |

| Partial tariffs: Smaller tariffs on targeted sectors and countries (Likelihood: 45%) | -0.2% | -0.3% | -0.2% | -0.2% | -0.3% | -0.1% | -0.2% | -0.1% |

| No significant new tariffs (Likelihood: 10%) | 0% for all | |||||||

Source - Oxford Economics, RBC Global Asset Management; data as of 2/10/25

In our view, trade policy is likely to remain a persistent source of downside risk to the economic outlook. Even without new tariffs, the mere unpredictability of what comes next in U.S. trade policy salvos alone can act as a headwind to economic activity through the “confidence” channels. Prolonged policy uncertainty could materially weigh on private sector sentiment, prompting businesses to defer or reduce investment and households to boost precautionary savings in anticipation of more turbulent economic conditions. This sentiment-driven drag on demand could slow growth even before any direct effects of tariffs take hold.