As they say, timing is everything. The largest-ever BRICS summit happened this week amid major geopolitical shifts, intense military conflicts in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and ongoing geoeconomic changes in the world—the most consequential period since the Cold War ended, from our vantage point.

Top officials from 35 developing countries, including 22 heads of state, gathered in Kazan, Russia for the 16th annual BRICS summit, many of whom seek to formally join the association or cooperate with it in one form or another. UN Secretary General António Guterres also participated.

It’s arguably one of biggest geopolitical events of the year and a gathering we view as rather consequential not only because of the participants, but also because of the decisions that were made and the ongoing development of the BRICS association.

Thirty-five developing countries attended the 16th annual BRICS summit in 2024

BRICS members

- Brazil

- Russia

- India

- China

- South Africa

- Egypt

- Ethiopia

- Iran

- United Arab Emirates

Other countries that participated

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Belarus

- Bolivia

- Congo

- Cuba

- Indonesia

- Kazakhstan

- Kygyzstan

- Laos

- Malaysia

- Mauritania

- Mongolia

- Nicaragua

- Saudi Arabia*

- Serbia

- Sri Lanka

- Tajikistan

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- Uzbekistan

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

* Saudi Arabia received a BRICS membership invitation in August 2023, subject to entry in January 2024. The country has not yet officially clarified its status in the association. It did not participate in the 2024 summit meeting for members only but did participate in the summit outreach sessions and various other events during the year.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, country delegation participation statements, first and second plenary sessions of the XVI BRICS Summit in the Outreach/BRICS Plus format

Beyond the hype: How BRICS sees the world

Summit after summit, there continues to be misinformation, disinformation, and confusion about what BRICS is and what it is not.

Before we assess the summit’s key developments, here’s our quick take on what BRICS is about and how it sees the world:

- It’s a group of developing countries that seek to form a “multipolar world.”

- These nations think the period that began after the Cold War ended—when the U.S. became the sole major power and basically led the global order (a period often described as a “unipolar world”)—is in the process of shifting or has already shifted into a new era.

- They believe they deserve a bigger say in global affairs.

- They highly value national sovereignty and seek to strengthen it for their own countries.

- They seek a “just world order” and a “fairer” global system based on mutual respect, and promote inclusiveness and consensus building.

- They desire deeper trade, financial, strategic, and cultural ties with each other.

- They support each other diplomatically where they agree. Where they don’t agree, they don’t exert excessive pressure on each other. They attempt to reason and persuade, not threaten.

- They don’t interfere in each other’s domestic affairs, and strongly object to when Western countries attempt to do this to their countries.

- They oppose what are called “unilateral economic sanctions” and secondary sanctions. Many BRICS members deem such sanctions as “illegal” because they are not approved by the UN Security Council.

- They are against using currencies—the U.S. dollar in particular—as a foreign policy weapon, and instead favor good old-fashioned diplomacy.

- They advocate reforming and improving—not eliminating—Bretton Woods-era global financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

- They believe the World Trade Organization has become dysfunctional and is badly in need of reform.

- They prioritize expanding the UN Security Council and restructuring other UN bodies to give countries in Asia, Latin America, and Africa a greater voice. They think Western-aligned countries should no longer have a disproportionate say in these bodies.

BRICS is not designed to be a formal political and economic bloc like the EU.

In fact, its members flatly reject the term “bloc” and don’t seek to become one. And they repeatedly assert that they’re “not against anyone.” India, in particular, does not want BRICS to be viewed as an anti-Western entity.

Nor is BRICS designed to be a formal military security alliance like NATO. There is no military component. Turkey’s participation in this year’s summit and desire to cooperate further with BRICS—the first and only NATO country to do so thus far—underscores this. If BRICS had military aims, any participation of a NATO country would be ruled out.

Some BRICS members, such as India, the United Arab Emirates, and Brazil, have very good relations with the U.S. and the collective West and intend to maintain strong ties.

Expanding the BRICS footprint

Regardless of how one sees the BRICS association and the various countries involved, we think it’s impossible to brush them aside.

The group has signaled it intends to expand by inviting certain countries among those who attended the summit to become a “BRICS partner,” which would be a new, next step toward the full membership process. In the past, BRICS membership invitations have required the consent of all existing members and some regional balance.

It’s our belief that other summit attendees would likely be invited to various BRICS events in the future or to participate informally in other ways. There were more than 200 events this year with more to come.

It’s also prudent to pay attention to BRICS members and any new partners given the dramatic geopolitical changes a number of these countries are involved in. Or, as the Chinese leadership likes to say, such changes that have not been seen in 100 years.

Economic heft equals clout

BRICS countries believe they deserve a bigger say in global affairs because collectively they have considerable economic heft and natural resources wealth, which they can translate into economic clout.

As Bloomberg News pointed out this week, “The world economy is set to rely even more heavily on the BRICS group of emerging economies to drive expansion, rather than their wealthier Western peers,” according to the IMF’s latest forecasts.

The IMF expects by far the biggest contributions to global GDP growth from 2024 to 2029 in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms to come from China, followed by India and then the U.S. The next tier is anticipated to be led by Indonesia, and then Russia, Brazil, Turkey, Egypt, Germany, Japan, and Bangladesh. Among these 11 countries, all but the U.S., Germany, and Japan attended the BRICS summit.

The economies of the nine BRICS member states already exceed the size of G7 economies in PPP terms, and the IMF forecasts the gap to widen.

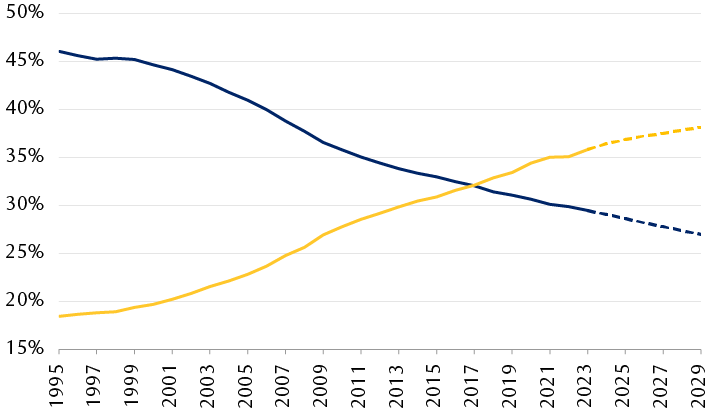

BRICS economic clout is increasing

Share of global GDP based on purchasing power parity in U.S. dollars*

The line chart shows the proportion of global GDP based on purchasing power parity for G7 and BRICS countries from 1995 through 2029; data from 2024 through 2029 are based on IMF projections. In 1995, there was a very wide gap between the two groups with the G7 at 46% and BRICS at 18.5%. The G7's GDP as a proportion of global GDP has declined meaningfully since then, while the BRICS countries' GDP as a proportion of global GDP has steadily climbed. The IMF projects this trend will continue through its forecast period of 2029. The G7 and 9 BRICS countries' share of global GDP was equal in 2017 at 32%. Thereafter G7 had declined to 29.5% and BRICS increased to 35.8% by 2023. By 2029, the IMF projects the G7 will decline to 27% and BRICS will rise to 38%.

GDP of the nine BRICS members surpassed G7 GDP in 2018, and the trend is expected to continue. Even before BRICS membership expansion, the previous five BRICS members had surpassed the G7 in 2021.

* Data from 2024 through 2029 are IMF projections.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, IMF database; data as of 10/24/24

Grain Exchange: Leveraging agriculture abundance

At the summit, BRICS members adopted Russia’s proposal to create a BRICS Grain Exchange.

We view this initiative as the association’s most important development since four new members (Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates) were added to the traditional grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa in January 2024.

- First, plans to roll out a new Grain Exchange demonstrate that BRICS is transforming into more than just a “club” of like-minded countries into an association that aims to incorporate practical platforms to advance economic interests and development.

- Second, it underscores that deeper integration is a priority, and raises the potential that BRICS institutions could be created in the future to provide at least somewhat more structure to the association.

- Third, we think the BRICS Grain Exchange will benefit developing countries that participate.

The trading of grains and other agriculture commodities has been dominated by U.S. and other Western exchanges for decades, which effectively set prices globally, and much of the goods are traded in U.S. dollars.

According to BRICS members, this new exchange is being created with the goals of:

- Forming “fair and predictable” grain prices

- Shielding participating countries from price speculation and artificial food shortages

- Protecting national grain markets from external interference

- Increasing food security for participating countries

- Facilitating grain trading in national currencies

The group left the door open to add other agriculture commodities to the exchange in the future.

BRICS member countries produce a considerable amount of grain; estimates from various aggregators of commodity production data range from 40 percent to 54 percent of global supplies. They also produce a significant share of the world’s meat, fish, and dairy products.

And with the nine BRICS member states representing 45 percent of the world’s population, they make up a meaningful portion of global grain consumption.

It’s also notable that Russia has proposed to create a separate BRICS platform for trading precious metals and diamonds—more commodities currently dominated by Western exchanges. Here too, BRICS countries have considerable production heft and resources.

Payments system: Much work to be done

BRICS members are working toward developing a blockchain-based system that would facilitate financial payments with each other. BRICS country officials are quick to point out this is not designed to be an alternative to the Western-run global SWIFT system; it’s simply intended to strengthen and enhance their own interbank communications systems.

It’s our understanding that financial, central bank, technology, legal, and legislative experts from BRICS member countries need to sort through an abundance of issues in order to fully develop a BRICS payments system. We believe their work will be careful and deliberate; no one is going to run ahead of the locomotive.

After the technical work is done, ultimately, BRICS heads of state will need to make decisions whether to launch the system and determine their respective country’s level of participation. There is no ETA on this initiative.

A “BRICS single currency,” often hyped in the press and by U.S. dollar doom-and-gloomers, is still not being formally considered by BRICS members and we don’t think it will be anytime soon for a variety of reasons. Leaders and top officials have made this clear many times, including in Kazan.

Forging closer ties on overlapping interests

BRICS members are also proposing new initiatives and deeper cooperation on existing bilateral and multilateral partnerships, including:

- The development of transit corridors and logistics (North-South Corridor, Northern Sea Route, and Eastern Maritime Corridor);

- electricity grid expansion, electricity transit among countries, and nuclear energy cooperation;

- developing a carbon trading system;

- preventative and advanced health care;

- artificial intelligence and cybersecurity cooperation; and

- humanitarian areas such as cultural and sport cooperation.

They also plan to expand the New Development Bank (NDB) of BRICS by adding an investment platform. It seems to us that the goal is for this so-called “BRICS bank” to take on more characteristics of its much larger cousin, the World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. We expect more public funding and private investment from BRICS country sovereign wealth funds, which could benefit developing countries that are members of the NDB.

Investing in the multipolar era

Developments at the BRICS summit in Kazan with this group of countries seeking to rebalance the global order, combined with the increasing trade protectionism of the U.S. since 2018, reinforces our view that the shift to a multipolar, more fragmented world argues for viewing portfolio allocations through a different lens.

As we explained in our May 2023 report “Worlds Apart: Risks and opportunities as deglobalization looms ,” the considerable ongoing geopolitical and geoeconomic changes call for a new way of thinking.

Sub-asset allocations within equities and fixed income should no longer be viewed through the lens of cooperative globalization that occurred in previous decades. We don’t think that era is coming back anytime soon.

In our view, this new era begs for more active asset management of country, industry, and company investment exposures. For example, we think the trends pose challenges for European economic growth, and the headwinds are already visible.

A number of strategically important industries seem poised to benefit from the geopolitical shifts that are taking place, and we list them on page 10 of this report.

But if protectionist trends in the West persist—like we think they will—global economic growth and equity market gains could be more muted than they were during the globalization heyday.