The core business of banking is mundane. Deposits are turned into loans, loans generate cash flows, depositors are repaid, and the whole cycle starts up again. The picture is a little more complicated with stock and bond investors included, but not by much.

Nothing about this is headline-worthy when done well, so we think it’s disconcerting to see small U.S. banks in the news. This round of falling regional bank stock prices comes amid concerns on banks’ exposure to commercial real estate (CRE), particularly office and retail properties that have been negatively impacted by changing work and shopping habits.

Bank stocks pull back; remain above recent lows

Despite an 11% drop in seven days, index is above near-term median

Line chart showing the performance of the KBW Regional Bank Index—an index of regional banking stocks—and also the median of 92.93 for the period of Jan. 13, 2023, through Feb. 7, 2024. Chart is showing an 11% decline from Jan. 30, 2024, to Feb. 7, 2024; latest reading was 96.49.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through 2/7/24

Problems, yes; catastrophe, no

Unlike most of the doom-and-gloom predictions that pop up from time to time, there is a kernel of truth to the narrative on CRE, in our view. Losses are real, and the impact will be felt. At the same time, we think press reports paint with too broad a brush when discussing the topic. There are huge differences between the events of 2008, for instance, and what we see as the reasonably likely outcomes for banks today.

At the level of publicly traded banks, we think it is very unlikely that large banks will be stressed, and we are not concerned with the solvency of the overall banking system. Instead, we think we are likely to see stress in some smaller banks, as rising credit losses could force capital raising that would, in turn, pressure security prices. Moreover, we would not be shocked to see larger, well-heeled banks scooping up CRE-troubled lenders at discounted prices.

In short, our view is not exactly “business as usual,” but is instead “resolution as usual,” with any problems in small banks largely dealt with by the normal capitalist process of resource reallocation.

First, the hard realities

CRE is a meaningful problem. Projects are closing and properties are being sold well below recent appraised levels. Bank lenders, who are typically the first in line for repayment, are almost certainly going to do better than project developers and junior lenders, but “better” is different than “good” and we’re expecting noticeable losses in the banking system. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), U.S. banks overall hold approximately $2.7 trillion in CRE loans, so this is not an issue that has been manufactured to sell newspapers.

Not only is the size of CRE exposure an issue for banks, but it’s also fundamentally different than the financing issues that hit regional lenders last March. After Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) failure, the need was to fund good assets as depositors left. That’s the textbook reason central banks exist, and the Federal Reserve could—and eventually did—provide the necessary loans to calm the waters. Last year, we pushed back on the idea that there was a crisis largely because the solution was obvious to us and easy to implement. Our view was that post-SVB, bank failures were a policy choice, not an economic requirement.

This time around, though, we are not dealing with an easy-to-solve funding mismatch, but a real problem: allocating the losses on loans that have gone bad and where the bank will never recover the full amount of the original loan.

Those losses go first to the capital layer. A well-reserved and capitalized bank in the U.S. will have equity to cover a loss of around 10 percent of its assets—some have more, some have a little less. Even in a recession, that’s usually plenty to deal with credit losses, but unexpected stress can quickly make the math look challenging: even if a relatively trivial three percent of assets are tied to the most problematic office loans, for instance, a simple calculation shows that nearly 25 percent of a bank’s capital could be at risk in a scenario of widespread defaults and low recoveries.

Any institution facing those kinds of losses would likely be forced to cut dividends and take other measures to shore up its balance sheet and appease regulators. Critically, though, we think a bank in that position should still be solvent—we’re discussing deep wounds, not necessarily fatal ones.

The sun will come up tomorrow

Despite the real problems in the sector, there is also a fair dose of hyperbole, in our view.

To begin with, CRE is an incredibly broad label, covering everything from cold storage facilities to apartment buildings. The current set of concerns is focused on three primary loan types: office space, retail, and multifamily housing. But even within this set of assets there is huge variation in the likely outcomes between individual properties. The $2.7 trillion figure from NBER is a theoretical maximum exposure; the practical risk in the banking system, we believe, is a small fraction of that amount.

Importantly, the risks on the largest loans have been distributed through securitizations and other transfer mechanisms. Outside of specialized funds, very few investors that we are aware of have large allocations to the most troubled CRE sectors. We believe this reduces—even if it does not necessarily eliminate—the pressure to sell assets at deeply discounted prices and minimizes the odds of contagion, where losses in one sector lead to forced selling in other markets.

Go big or stay home?

For the banking system overall, we believe there is sufficient capital to absorb a complete write-down of the entire $2.7 trillion in estimated CRE exposure, although that would leave it essentially drained of equity. The issue, of course, is that the allocation of capital does not necessarily match the allocation of likely losses. We believe this problem is particularly acute at small lenders.

To begin with, smaller banks are the major players in the CRE space. According to the NBER, banks with less than $1.4 billion in assets account for about $419 billion of the banking system’s exposure; this corresponds to about 25 percent of smaller bank assets by our calculations. In absolute terms, the largest banks—those with over $250 billion in assets—have greater CRE exposure, but it amounts to less than five percent of their overall investments, according to NBER data.

Small banks’ reliance on CRE is a double hit. Not only are they seeing large write-downs on existing loans, but pressure from investors also makes it difficult to aggressively originate new loans, reducing earnings and making it more difficult to replenish the coffers. Larger banks, by comparison, have diverse revenue streams and the impact of diminished CRE lending is, on average, barely noticeable.

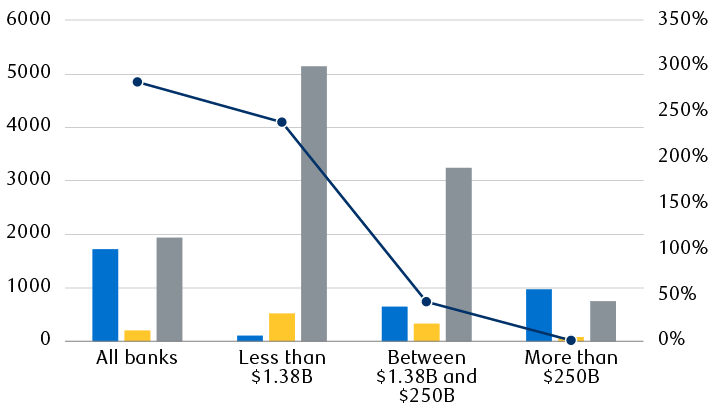

Large number of banks have CRE risk, but large banks have less of it

Bar chart showing exposure to commercial real estate, measured both as a percentage of assets and against a hypothetical 10% capital position, as a function of bank size. The data indicates that banks with less than $1.38 billion in assets have the highest exposure to CRE while banks with $250 billion in more assets have the smallest exposure to the sector. Chart also shows there are approximately 4,000 banks with less than $1.38 billion in assets, about 725 banks with assets between $1.38 billion and $250 billion, and only 13 banks with assets more than $250 billion.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, National Bureau of Economic Research; data through 12/31/22

Depositor and investor concerns about small bank exposure to a troubled asset class also raise the risk of money being pulled from these institutions, much like we saw after the fall of SVB. This time around, however, it will not be as easy for the Fed to swoop in and provide assistance, given the concerns around the ultimate repayment of the loans, a factor that was absent in last year’s Treasury bond-focused turmoil. Even banks that continue to find funding may need to pay more for it, adding to financial stress. One bright spot we see for these banks is that after last year’s depositor flight, there’s reason to believe that remaining depositors are stickier and may stay with the bank despite negative headlines.

A final issue, particularly for the smallest community banks, is loan concentration. Average loan sizes in the CRE world are much larger than in retail banking, so even a few problem loans can have a meaningful impact on the results and capital of a small bank. As an example, New York Community Bank was in the news recently following a nearly ninefold increase in loan loss provisions, driven partly by two CRE credits, as well as increased reserve build for the loan portfolio in aggregate. And that’s an institution with over $100 billion in assets; for a smaller community bank, a single bad loan is potentially a meaningful event.

Many paths ahead

Despite the realities and the risks, we think widespread bank failures from CRE exposure remain unlikely. We see small banks coming under pressure on two fronts: rising losses on CRE loans cutting into capital levels, while more expensive funding and reduced lending opportunities serve as a headwind to earnings. This may lead to some bank failures, but we do not foresee anything that would unduly stress existing mechanisms to resolve troubled banks.

We think the largest banks, by contrast, will likely do fine in any CRE pullback, as their lower exposure and cheaper funding allow them to take advantage as opportunities arise. We think the U.S. banking system is healthy and will be able to weather the likely CRE volatility ahead.