Key points

- Living longer has exposed new health conditions unknown to past generations. Scientists’ attention has turned to extending “healthspan,” or the number of years a person is healthy in old age.

- Since the turn of the 21st century, scientists have gained greater insight into the biological mechanisms of ageing. As biological damage accumulates and remains unrepaired, age-related disorders, such as heart disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and neurodegenerative illnesses, arise.

- Three approaches to tackle age-related diseases seem to hold much promise: senolytics, stem cell regeneration, and the lengthening of chromosome ends. In addition, biotech innovations in other fields which enable more efficient treatment of chronic illnesses such as cancer also play a role in expanding healthspans.

- The most exciting biotech innovations may not necessarily make for investments with the most promising potential upside. Investors should also assess the competitive landscape as well as the legal and regulatory environments to gauge whether a franchise is likely to be sustainable for many years.

Emerging technological advancements are driving innovations all around us, transforming how we live, work, and interact with one another, today and in the future. RBC Wealth Management’s “Innovations” series examines these agents of change and how they can open up compelling investment opportunities.

This inaugural report in the series focuses on scientific advancements related to ageing. Over the past 20 years, scientists have acquired a much fuller understanding of the biological pathways of ageing and are developing ways to slow, stall, and possibly even reverse its impact on the body and mind. We dive into a few of the most promising advances and explore the link between scientific breakthroughs and intriguing investments.

From lifespan to healthspan

Life expectancy has doubled over the past 150 years thanks to medical and social progress. Infant mortality has largely been defeated thanks to cleaner water, better nutrition, and more advances in and greater access to vaccines and antibiotics. Today, children born in developed nations can expect to have an even chance of living past their 80s.

Living longer has brought with it a bevy of conditions that past generations—who were prone to die from war, accidents, famine, or epidemics—had virtually no experience with. Scientists’ attention has thus turned to extending healthspan, or the number of healthy years before the end of life. Between 16 percent and 20 percent of life is spent in a state of daily battle against an increasing burden of chronic diseases in late life, according to a 2018 article in Nature, a peer-reviewed scientific publication.

Beyond the distress this causes patients and caregivers, health care costs are surging. In 2024, total U.S. health care costs for all individuals 65 years and over suffering from Alzheimer’s disease will reach $360 billion, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. This represents eight percent of total U.S. health care costs, or as much as cancer and cardiology combined. The Alzheimer’s Association also points out that millions of family members and unpaid caregivers already provided 18.4 billion hours of care, valued at $346.6 billion in 2023.

With populations ageing, these costs will keep on rising, putting a strain on society and the economy. The global population of people 60 years and older will reach 2.1 billion by 2050, according to the World Health Organisation. No country will experience this more acutely than China, which is expected to have more than 500 million people over the age of 60 around mid-century.

Even today, the need for benefits and assistance is putting immense pressure on health care and social security systems in most ageing societies. Greater demand for these services may well require higher taxes and/or increased government debt burdens, and in turn likely push up long-term interest rates. Where a government does not or cannot provide old-age care and end-of-life services, households will likely increase their savings rate, potentially draining consumer demand.

Successfully lengthening healthspans could alleviate cost pressures on both governments and households while adding more years of satisfying life that can bring opportunities to learn and develop new skills, as well as the prospect of staying productive longer.

Much improvement everywhere

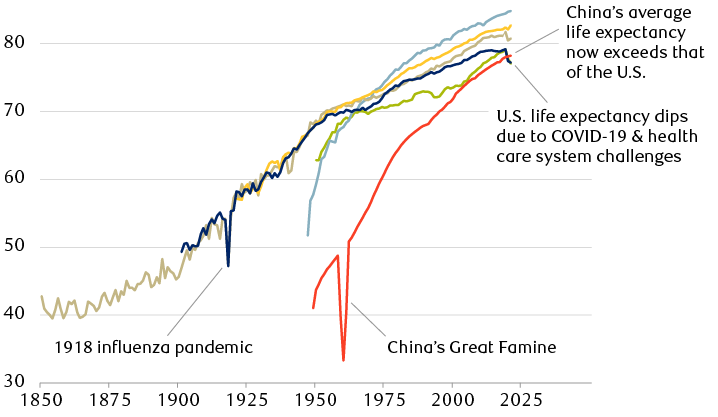

Life expectancy at birth since the 1850s

The line chart shows historical life expectancy at birth for Europe, Canada, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, and China through 2021. The first years shown and frequency of data vary by country. The earliest data are from the mid-1800s, and data is annual for the United Kingdom since 1850, the United States since 1901, Canada since 1921, and the remaining regions since roughly 1950. Life expectancy in all countries shown has followed a similar upward trajectory and is now between 77 and 82 years. Notable deviations from this trend highlighted include the 1918 global influenza pandemic and the famine in China in the late 1950s. U.S. life expectancy dipped due to COVID-19 and health care system challenges, and China’s life expectancy now exceeds that of the U.S.

Source - Our World in Data

What is ageing?

In Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a character is asked how he went bankrupt. He answers, “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” The same can be said about ageing. By 60 years old, most people have at least one age-related condition. By the age of 80, most have several.

Scientists have come up with two hypotheses to explain the cause of ageing from a biological point of view. Some contend ageing is caused by the same developmental processes that are useful early on in life, only that they continue to run haphazardly into adulthood, causing the deterioration that comes with old age. For instance, the bone loss that women experience after menopause could be the continuation of the processes that drew calcium from the skeleton to produce milk in breastfeeding mothers, or far-sightedness in middle age could be caused by the lenses of the eye continuing to grow into adulthood.

Others posit that ageing is the gradual loss of the body’s ability to repair itself. When it is young, the body repairs damage to ensure genes can be passed on to the next generation. But an ageing body loses the ability to repair itself efficiently, and damage starts to accumulate.

While scientists still debate the processes that drive ageing, they tend to agree on the physiological details of ageing, i.e., the cellular changes which accompany the progressive decline in physical functions over time.

In “Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe,” Carlos López-Otín, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Oviedo in Spain, led a team that produced a widely used list of the characteristics of ageing in 2013. They recently updated it to account for the advancements in biological sciences since initial publication. Twelve “hallmarks” were identified that worsen with age, accelerate if stimulated, and seem to slow down with treatment.

By dividing up the problem, it may be possible to treat each hallmark individually, thereby enhancing prospects of cracking the ageing code. In practice, many of the hallmarks are tightly intertwined, such as chronic inflammation, DNA damage, and dysfunction of the mitochondria—the powerhouses of cells—which enhances the challenge.

In a nutshell, some ageing mechanisms include:

- Genetic mutations accumulating

- Chromosome ends crumbling

- Tissue being blocked with debris

- Cells becoming cancerous while others enter a zombie-like state, harming healthy cells

- Stem cells no longer dividing and becoming unable to create new cells

- Mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells, falling into disrepair

- Chronic inflammation creeping through the body

- Gut microbiome becoming less healthy

Eventually, age-related damage exacerbates the body’s vulnerabilities and can lead to chronic disorders such as heart disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and neurodegenerative illnesses.

Hallmarks of ageing

Terms

Definitions

Concepts

Genomic instability

A genome is the complete set of genetic material in an organism, and includes the DNA, genes, and chromosomes.

Genes are often thought of as traits inherited from parents, but they primarily function as units of information.

Genomic stability ensures the transmission of genetic material from one generation to another through a perfect replication of genetic material and a repair mechanism for any damaged replication.

Genomic instability refers to the persistent accumulation of mutations and the failure of the repair mechanism to correct them.

For instance, mutations that enable cells to reproduce unbridled can cause cancer. Cells can only reproduce or undergo division 40–60 times (except stem cells and cancer cells).

Telomere attrition

Telomeres are protective caps found at the ends of chromosomes. They help protect the genome, the genetic material, and help guard cells against mutations. Telomeres shorten every time cells divide.

The shortening of telomeres limits the number of future cell divisions, ultimately causing the number of healthy cells to decline.

Epigenetic alterations

Epigenetic markers are labels, akin to bar codes, located at specific sites on chromosomes, which tell cells what genes to use.

Changes in epigenetic markers can affect gene function. For instance, alterations can change the pattern of gene expression in a way that may encourage the development of cancers.

Loss of proteostatis

Proteostatis is the process that ensures a cell is supplied with the right proteins in perfect condition and in the right proportions.

Loss of proteostatis leads to cells producing proteins in imperfect forms and inappropriate numbers. Accumulations of imperfect proteins seem to be the cause of several diseases of old age, such as Alzheimer’s or cataracts.

Disabled autophagy

Autophagy is the process of waste disposal that cells use to eliminate their damaged components.

When autophagy mechanisms fail, debris accumulates.

Deregulated nutrient sensing

Deregulated nutrient sensing refers to deterioration in the cell’s ability to sense nutrients.

Deregulated nutrient sensing disrupts the cell’s ability to regulate its energy metabolism.

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondria are the powerhouses of cells, responsible for respiration and energy production.

Dysfunctional mitochondria become less efficient at producing energy.

Cellular senescence

Senescent cells are those that no longer divide but continue to live on in a zombie-like state instead of self-destructing. Proteins are usually considered an essential part of diet, but they also give the body form and strength and carry out most of the chemical reactions essential for life.

Senescent cells can cause damage to nearby healthy cells by pumping out inflammatory proteins that destroy healthy tissue around them.

Stem cell exhaustion

Stem cells are the reserves from which new cells can be produced and regenerate tissue. They are particular in that they continuously divide—unlike other non-cancerous cells, which only divide 40–60 times.

When stem cells stop dividing, they are unable to generate new cells to replace the old ones.

Altered intercellular communication

Intercellular communication takes place when cells communicate with one another to enable an individual to function.

The systems used by cells to coordinate their actions start to unravel and eventually stop working.

Chronic inflammation

Inflammation is the body’s process of fighting against things that harm it, like infections, injuries, and toxins. Cells suffering from genetic instability or senescence can also start this process, causing chronic inflammation.

By starting the process to fight perceived harm, cells provoke inflammatory responses, but as there is no infection to fight, the response causes problems.

Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis is the disruption of the microbiome, or the collection of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes that live in the gut.

As the microbiome becomes less healthy, the communications between its microbes and the body go wrong.

Source - Carlos López-Otín et al., “Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe,” Cell 186, no. 2 (Jan. 3, 2023); Venki Ramakrishnan, Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality (Stoughton, 2024)

DIY healthspan extension (biohacking)

As the genetic pathways and biochemical processes of ageing become better understood, a culture of “do-it-yourself” healthspan extension has emerged. “Biohackers” are people who explore using existing pills and supplements in the hope of improving their healthspan, and largely operate outside the medical sphere.

It’s recently become commonplace to carefully calibrate what one eats to improve the health of one’s microbiome. Intermittent fasting is an increasingly popular method that aims to induce autophagy, the waste disposal system that cells use to rid themselves of damaged components. Clinics which offer blood plasma transfusion therapies to boost cell or tissue rejuvenation (i.e., epigenetic rejuvenation) are becoming more prevalent. This technique is based on findings that aged mice injected with blood from young mice experienced a reversal of biological ageing. However, evidence of the success of this method as applied to humans remains inconclusive.

Many scientists are concerned there is too much hype around biohacking and its unconventional approaches.

Most promise

In his recently published book Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality, Venki Ramakrishnan, a molecular biologist and co-winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, highlights three approaches which he judges as most promising:

Senolytics

This class of drugs is designed to target senescent cells—those that have ceased dividing. Non-cancerous cells reproduce themselves 40–60 times, after which cell division stops. The cells do not die but rather enter a zombie-like state called senescence. A young body clears out these decrepit cells by either triggering a self-destruction process or by using the immune system to kill them off. But both of these natural clearing-out processes become less efficient with age.

Senescent cells which accumulate in the body secrete inflammatory molecules, dripping destructive compounds into nearby tissue and inhibiting the proper functioning of healthy cells in close proximity. Science suggests that senescent cells are at the root of many ageing-related diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and cataracts.

As a first step, scientists are focusing on drugs and supplements already approved for human use for different indications to try and see if they can clear out senescent cells. There are as many as 20 ongoing clinical trials on humans, according to an August 2022 article in Nature Medicine.

Stem cell regeneration and cellular reprogramming

Another approach focuses on rejuvenating or reprogramming the cells, capitalizing on recent developments in stem cell science. Stem cells are the reserves from which new cells can be produced to regenerate tissue, and are already widely used in regenerative medicine. Many scientists are searching for applications in the hope of countering ageing.

Researchers are seeking to reprogram cells so as to try and revert them to an earlier stage capable of regeneration. Blood stem cell transplants have been found to extend the life of mice by 20 percent.

Telomerase reactivation

Telomeres are segments of DNA at the end of each chromosome. Every time a cell copies its chromosomes and divides, telomeres become slightly shorter. When telomeres get too short or wear out completely, cells may stop dividing and become senescent.

Scientists are focusing on reactivating telomeres, to prevent them from shortening as cells divide. An enzyme, telomerase, has been discovered that can lengthen telomeres. This enzyme is usually only active in cells, such as stem cells, that divide a very large number of times, unlike normal cells. As the body deactivates telomerase as part of the ageing process, scientists are exploring whether it is possible to reactivate it in an effort to prevent the shortening of telomeres.

Good things come to those who wait

While Ramakrishnan is optimistic about these cutting-edge methods of combating ageing, it could take at least a couple of decades to create the necessary and successful therapeutics, in his view. The vast majority of experimental drugs that prove successful in labs and on mice or other animals fail once applied to humans—and even those that work very rarely make it to market.

In the meantime, RBC Capital Markets, LLC Senior Biotechnology Research Analyst Luca Issi points out that healthspan can be materially expanded via better diagnostics, earlier intervention, and improved therapies for diseases such as cancer and heart disease.

Moreover, he asserts that biotech innovations in fields beyond ageing have flourished, enabling more efficient treatment of several conditions. For instance, multiple drugs have been approved in the area of genetic medicine, which focuses on individual genes that cause diseases and manipulates them to make an impact for patients. So far, approvals have mostly been given to treatments for rare diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy and beta-thalassemia, an inherited blood disorder. But as the technology advances, approvals for treatments of more common illnesses, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, or eye disease, are around the corner, in his view.

A good investment?

Investing in the “combating ageing” theme can be implemented via the biotech industry. Still, Issi points out that the most exciting biotech innovations may not necessarily translate into the most promising investments. Those companies that can successfully prioritize diseases with a meaningful unmet need and potentially large patient population, and execute on well-designed clinical trials are more likely to emerge as winners, in Issi’s assessment.

He believes investors should also monitor the competitive landscape to evaluate whether a franchise is likely to be sustainable for many years. Assessing other secular changes and disruptive forces, such as technologies or legal and regulatory environments that would potentially have a transformational impact on the value of both existing and emerging biotech franchises, is also key to gauge whether investments are promising.

Other industries may experience shifts in demand as the population ages and play into the theme as well:

- Wealth management may well find it has a captive audience as individuals will need to consider how not to outlive their savings.

- Homebuilders in various geographies may experience changing demand for residential space, if the experience in Japan is anything to go by. The Japan Times reported in May 2024 that there are nine million vacant homes in the country, largely the result of ageing. Housing demand to accommodate multi-generational households may rise in some regions, while others may see growing demand for single-occupancy homes.

- The ongoing revolution in biological sciences may also boost demand for life science real estate (i.e., lab and office space for tenants involved in scientific discoveries).

So close, yet so far

With scientists having clearer insight into the biological pathways of ageing, the prospects for positive healthspan outcomes appear more promising than 20 years ago thanks to a proliferation of effort including hundreds of companies exploring dozens of different compounds, and human clinical trials that are underway. Medical breakthroughs are possible, as the recent drugs targeting obesity—a condition which eluded treatment for decades—have demonstrated.

In the meantime, a good diet, exercise, and sound sleep seem to be the best strategy for those aspiring for a long and healthy life.